Eleven Black Women: Why Did They Die? — An Interview with Black feminist socialist Barbara Smith

Barbara Smith, one of the key contributors to contemporary Black feminist thought, formed the Combahee River Collective in 1974 to address Black women's interlocking oppressions.

(The Combahee River Collective’s first Black feminist retreat in July 1977, in South Hadley, Massachusetts. Second, from the left, is Barbara Smith. Photo courtesy of Margo Okazawa-Rey).

In 1979, eleven Black girls went missing between the months of January and May from the Roxbury neighbourhood in Boston, Massachusetts. For several weeks, community inquiries were made through official channels before it became evident that local institutions failed to adequately investigate these tragic crimes. With a lack of police investigation or news media coverage, a group of Black feminists instead took it upon themselves to organize around the issue.

One of the major actions around the 1979 Roxbury murders was led by the Combahee River Collective (CRC), a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization based in Boston between 1974 and 1980. The CRC was founded by Barbara Smith, alongside her twin sister, Beverly Smith—a Black feminist writer, academic, and theorist—and Demita Frazier, a Black feminist writer, teacher, activist. It was instrumental in broadening the limitations of feminist thought and sparking its third wave by challenging single-issue white, middle-class feminism; single-issue Black nationalism movements by cis-hetero men; and a single-issue gay rights movement. The collective was committed to combating racial, sexual, heterosexual, cis, and class oppression by compelling us to consider interlocking systems of oppression — and, in doing so, laid the foundations for intersectional feminism. Members included Audre Lorde, Cheryl Clarke, Akasha Hull, Margo Okazawa-Rey, and Chirlane McCray.

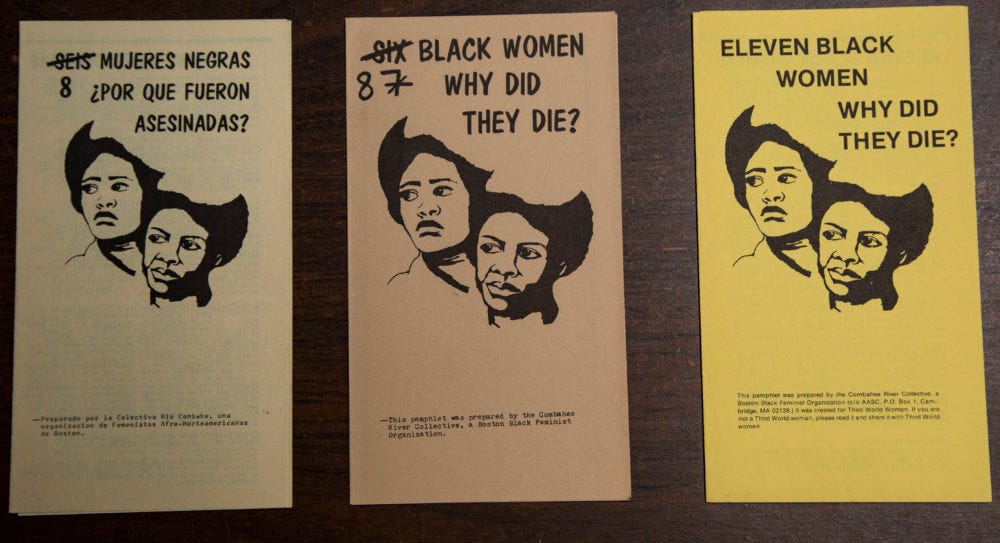

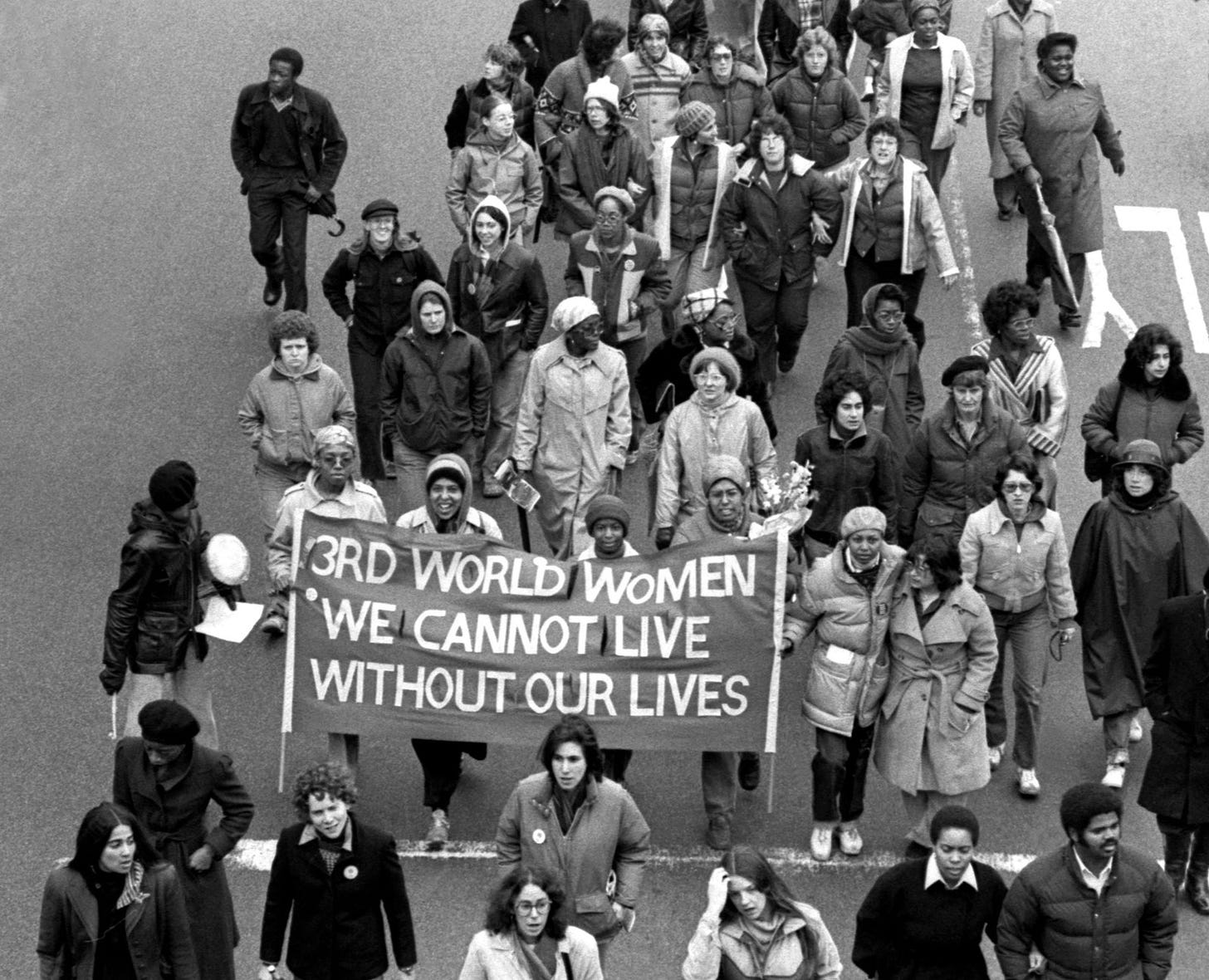

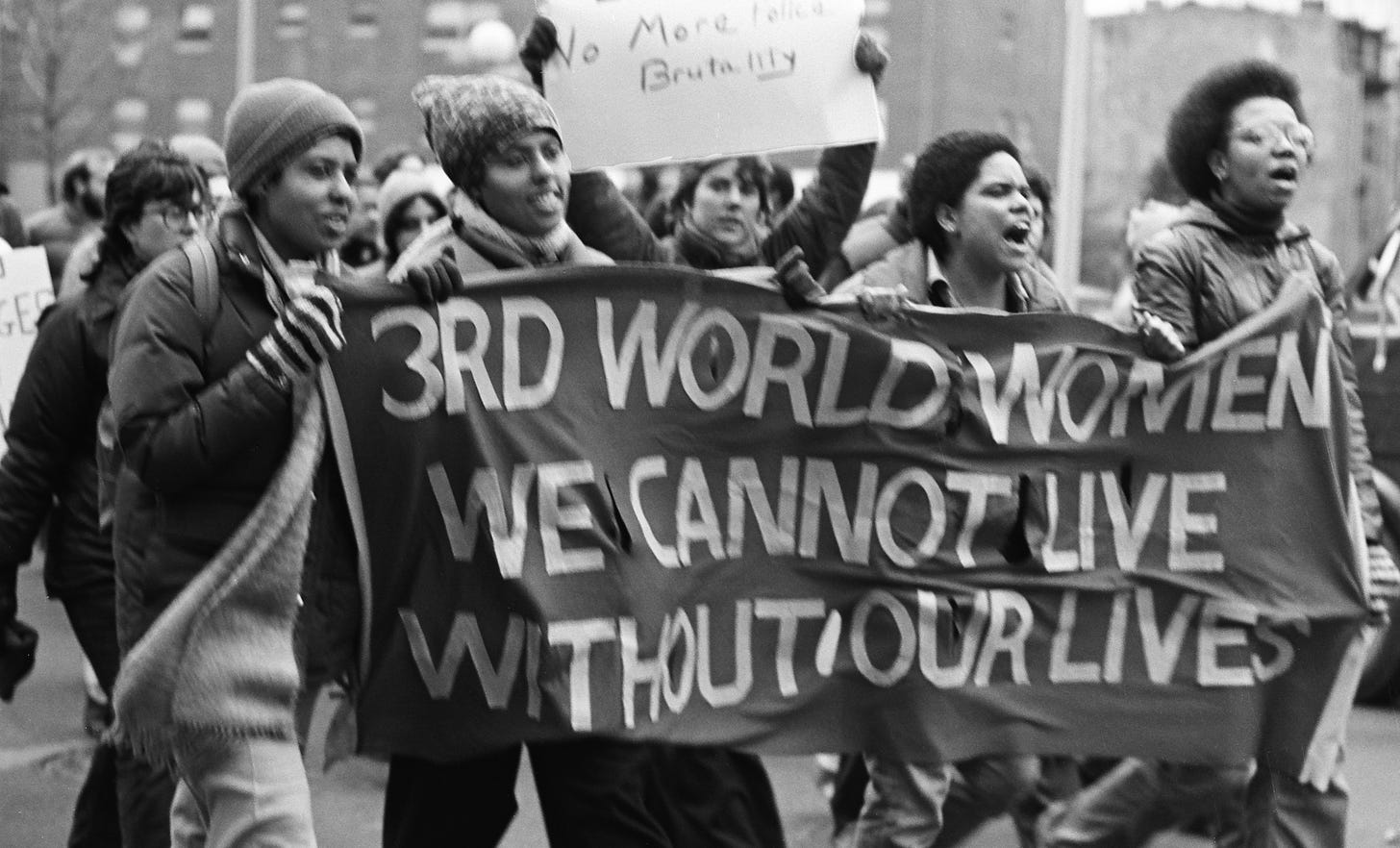

On April 28th, 1979, CRC organized a 500-person march at the Boston Common where they distributed a pamphlet, Six Black Women: Why Did They Die? (1979). The march was in protest of the increased racial and sexual violence targeting Black women in the affected area (and the total lack of institutional response). The pamphlet offered community members tools and resources to protect each other from racialized patriarchal violence; it also spelled out the structural conditions that led to the ongoing rape-murders of Black women. Six Black Women: Why Did They Die? (1979) spelled out the conditions in which the city failed to contend with the serial cases of Black women going missing or murdered. The CRC wrote: “The mother of a fifteen-year-old, one of the first two victims, says that when she reported the disappearance of her daughter to the police they hesitated to file a report claiming that the girl had probably gone off with a pimp. Within two weeks, her body was found, to be followed by twelve more in a period of five months.”

Leading up to this moment was a full-swing civil rights movement and the second wave of feminist thought, both of which failed to adequately address the interlocking systems of oppression affecting Black women. This conjuncture signified a lack of the intersectional analysis that has become integral to contemporary feminist thought and Black liberation struggles. In 1977, the CRC released their renowned Combahee River Collective Statement, which has since become a canonical text in feminist thought. I have returned regularly to the Combahee River Collective Statement for the better part of the last few years, as a student and Black feminist educator. Over the last four decades, the Combahee River Collective Statement and pamphlet have become embedded into the gender studies canon. And, unfortunately, their words remain relevant in a world that continues to neglect the gendered violence endured by Black women through and across all borders.

"The Combahee River Collective was a bridge for the different communities. It cannot be underestimated how Combahee — this Black feminist, socialist, radical organization — was the bridge during a time of incredible crisis in the city of Boston." — Barbara Smith

Before the legal theorist Kimberle Crenshaw coined ‘intersectionality’ in 1989, the Combahee River Collective asked us to address interlocking systems of oppression. Smith named the Combahee River Collective after reading Earl Conrad’s Harriet Tubman, Conductor on the Underground Railroad. After learning about Tubman’s self-led military campaign to free 750 enslaved peoples through the Combahee River in South Carolina, she wanted to name their movement to honour the continuum of Black women’s struggles for liberation.

(A 500-person march on April 28th, 1979, organized by Combahee River Collective at the Boston Common.)

Barbara Smith is an American feminist writer, teacher, activist, independent scholar, author, community organizer, and publisher. For almost five decades, Smith has diligently fought against the imperialist white-supremacist, hetero-capitalist patriarchal structures that have and continue to allow so many Black women and girls to go missing, or murdered, with little public concern. In 1994, she won a Stonewall Award for her activism; and, in 2005 was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for her contributions as a Black feminist organizer.

At the suggestion of her friend, Audre Lorde, Smith helped create Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1981, publishing works by over one-hundred thousand women of colour—including celebrated writers and thinkers like Angela Y. Davis, Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, Audre Lorde, and Alma Gómez. (The press became inactive soon after Lorde’s death in 1992.) Prior to becoming a publisher in the 1980s, Smith taught courses on Black women writers in the early 1970s at Emerson College in Boston before forming the Combahee River Collective in 1974.

In 2017, within a short period of time, a number of cases of missing Black women in DC seemed eerily reminiscent of the events in Roxbury almost four decades prior. Community members took to social media, decrying the same police and media neglect that had accompanied the earlier spate of violence. As I attempted to report on the rising cases of missing Black women in DC, I reached out to several Black feminists across North America (including Christina Sharpe, Kim Ninkuru, Raquel Willis and Barbara Smith) to explore how and why Black women continuously face the threat of femicide, or, as Barbara Smith says, “the wonderful combination that patriarchy gives us: the rape-murder.”

Smith and I spoke on the phone for over an hour in July of 2017 for a story I was writing for VICE. After weeks of writing, the editor suggested the topic was no longer relevant or timely. (The editor specifically said we needed “a new timely hook supporting why we decided to publish this piece now.”) We needed to wait for another murder. Instead, I asked to kill the piece. Barbara Smith—a living elder—and the topic of our conversation—the real lives at stake—required a level of care and criticality that wasn’t being offered at VICE. For four years, I have desired to share these conversations trapped in my archives.

Two years ago, I shared a link to this place with some of you with the intent of sharing new essays. This was during a hiatus I had taken from public writing. The idea of returning to my practice filled me with anxiety. Sometime last year, I overcame it as I returned to cultural reporting. I’ve also thought a bit more about what I want this space to be: a place for me to loosely share notes, snippets, and ruminations on conversations, art, and thinkers that are circulating in my mind.

At the time that I am writing this, the number of missing Black women and girls is rising in Toronto without much intervention. At the same time, advertisements for women who are being trafficked have appeared across subways and bus shelters in the city. This is one month after the state of Minnesota became the first in North America to create a task force on missing and murdered Black women and girls. For my first newsletter — somewhere between Black History Month and Women’s History Month — I’m offering snippets of my chat with Barbara Smith on how Black feminist organizing, particularly in the wake of the 1979 Roxbury murders, cultivated bridges during a time of crisis in the city of Boston.

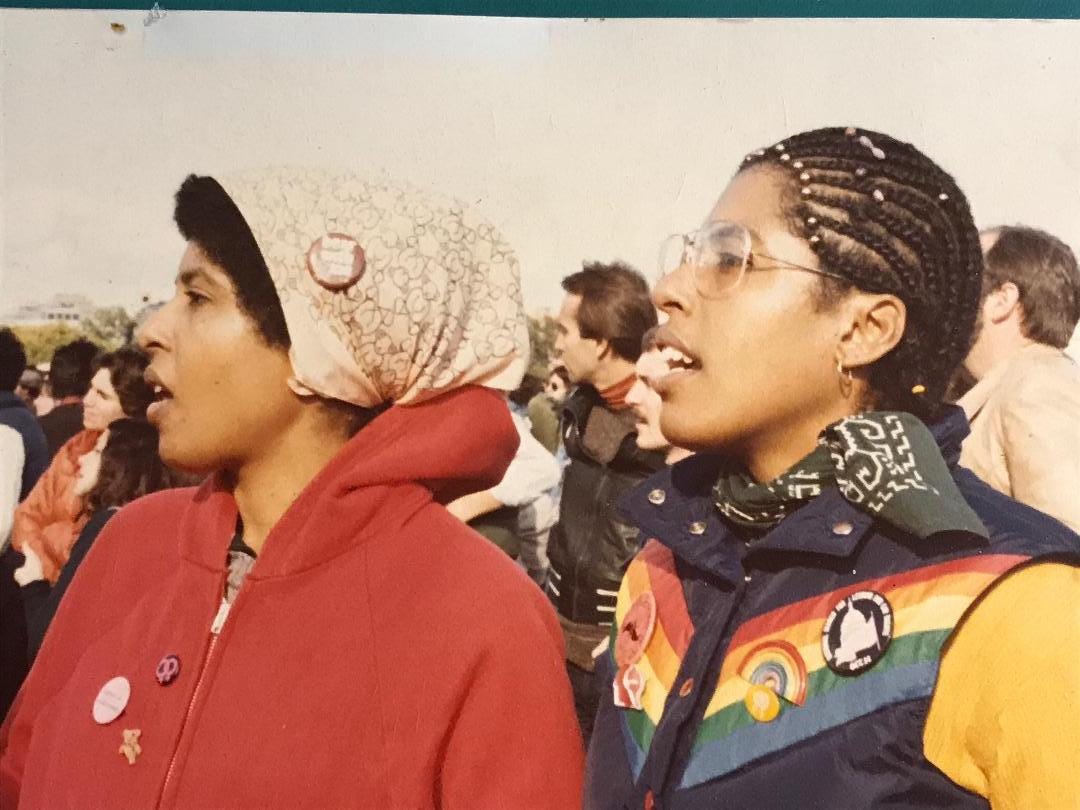

(Beverly Smith and her sister, Barbara Smith, at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, October 14, 1979. Photo by Tia Cross.)

Please donate and/or share Barbara Smith’s Caring Circle Patreon, a fund created to support an elder Black feminist organizer through retirement.

Huda Hassan: The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was formed in 1974, and in 1977 you released the famous CRC statement. How did this statement come about?

Barbara Smith: [Combahee River Collective] were committed to political organizing and activism. We were building Black feminism locally — and as it turned out, across the United States. We were asked by a wonderful person, who is still with us, (feminist activist and scholar) Zillah Eisenstein, to write the statement. She's a political science professor, but she was working on her first book, Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism (1978). We knew each other before she asked our collective to write something for the book, and it turned out to be the Combahee River Collective statement. That was a time when political movements and organizations put out statements. We still see this. It's something that is often done by people who are politically active. But what we did, of course, was unique because Black feminism wasn't generally acknowledged as being significant or even existing. The Combahee River Collective Statement is still used. We think it had a lot of impact on how people understand the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality, as well as other intersecting oppressions and identities. We may very well have ended up writing such a statement, even if we had not been invited to do so by Eisenstein. I think that the fact that she asked us to do it was more than fortuitous.

HH: Could you tell me about your understanding of, and your response to, the murders in 1979 that began in Roxbury and spread across Boston?

BS: One of the things that made the murders so visible is that things were happening quickly; a great number in such a short period of time. This was not a serial killer; there were several people identified as having perpetrated the murders. Some of the murders were never solved and have never been solved. It was such a concentration of violence against Black women in particular; the fact that the murders were originally defined by members of the Black community as being racial murders only, yet all the people who were murdered were women and were sexually assaulted… This is the wonderful combination that patriarchy gives us: the rape-murder.

We were going to join efforts to speak out about the murders and noticed who paid little or no attention to them. The Boston Globe paid no attention to the murders. The police department did not prioritize them. We were upset about the neglect and [the lack of] concentrated energy toward addressing the issue or being supportive to those of us in our community who were targeted by the crimes.

The pamphlet that we created — originally titled Six Black Women: Why Did They Die? (1979) — was written in response to going to rallies [about the] murders and having them be described solely as racial crimes. No mention of violence against women, gendered violence, or anything like that. And then, having men suggest, as a way that we could protect ourselves and avoid being hurt or killed, was to be dependent upon male protection. We were not having that as young Black feminists.

I went home and started working on what became the pamphlet. There was no email in those days. There were no fax machines. After writing a draft, I read it to other members of the collective one by one. They concurred. They had some input, and the next day (on a Monday) I called up a place in Boston called Urban Planning Aid, [an organization dedicated to] helping movement groups and neighbourhood groups. They helped with technical assistance around publicity and other kinds of things that would be useful for grassroots organizations. One of the things they did was graphic design if you needed to get a flyer or brochure done. I called up UPA and was told by the graphic artist how many characters across the column I needed to type in because it had to be the perfect copy. The technology we used was typewriters; there were no personal computers in those days, of course. You corrected something physically with whiteout.

I'm explaining the technology to you because people think the only reason that organizing is successful is because of the technology that now exists. That is not accurate. The technology that you use at the time is the state of the art for the time. We were using the state of the art. It sounds old, creaky, and impossible — so what? It was what was available.

The thing that made the Six Black Women: Why Did They Die? (1979) pamphlet and organizing successful was our passion for justice; passion to eradicate violence against women. One of the things that we were aware of, that many in our communities were not, was an analysis about violence against women. There were organizations that addressed violence against women, and we wanted to bring them together, so we did in a powerful way. We wanted to bring together people of colour, aware of and living under white supremacy, with people in the women's community and the women's movement who were just probably doing everything they could to eradicate violence against women. We were the bridge.

HH: Tell me more about Combahee River Collective being a bridge.

BS: The Combahee River Collective was a bridge for the different communities. It cannot be underestimated how Combahee — this Black feminist, socialist, radical organization — was the bridge during a time of incredible crisis in the city of Boston. We brought together parts of the Boston community and members of various movements and organizations that had an impact beyond the crisis period of the murders.

I moved from Boston in 1981. And subsequently, there was a great activist in Boston, Mel King. He coined the concept of a rainbow coalition and ran for mayor in 1983. He did not win. But he ran again when I was living in New York in the early 1980s. And everything I heard from my friend, Lawson, is that it was an incredibly vibrant campaign; so many people came together, so much like the kind of coalitions that we dealt with that we were able to build during the horrific period of the murders of Black women. We really were a bridge, and I think made a real difference in the political culture of Boston during that period. Even if your memory fades, and you have many chapters in the long book of life and struggle, Combahee River Collective played a really important role during that time.

The only thing I know to do about anything that falls into the realm of grace and justice is to organize. It's hard to see when violence, discrimination, oppression and exploitation are still occurring. Organizing works because those who are now in power, like this creature in the White House, are doing everything possible to eradicate and dismantle everything we have worked for about the last 100 years—as far as increasing justice in the United States and extending rights to people who, at different points in US history, had none. We have young people right now holding the state accountable. Organizing is important.

This interview excerpt is from June 2017 and has been condensed for clarity.

Some offerings:

“Four Women” by Nina Simone. A song.

Why do cases of missing Black women rarely make US headlines? A short video.

Minnesota became the first state in the nation to create a task force on missing and murdered Black women and girls. Some news.

“Alexis Crawford’s Untimely Death Exposes the Systems That Failed Her” by journalist Clarissa Brooks: https://zora.medium.com/alexis-crawfords-untimely-death-exposes-the-systems-that-failed-her-f2763beb0fbe

“Cyntoia Brown Is Getting Back The Childhood She & So Many Young Black Girls Never Had” by journalist Clarissa Brooks

“'Cops only tackled me and my friend': why a dark skin tone makes activism dangerous” by journalist Clarissa Brooks

“Why Black Student Organizers Are The Future—And The Present And The Past” by journalist Clarissa Brooks:

Please donate and/or share Barbara Smith’s Caring Circle Patreon, a fund created to support her financially through retirement.