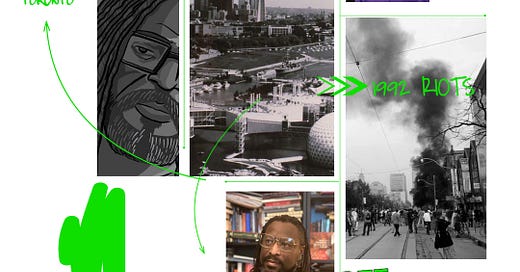

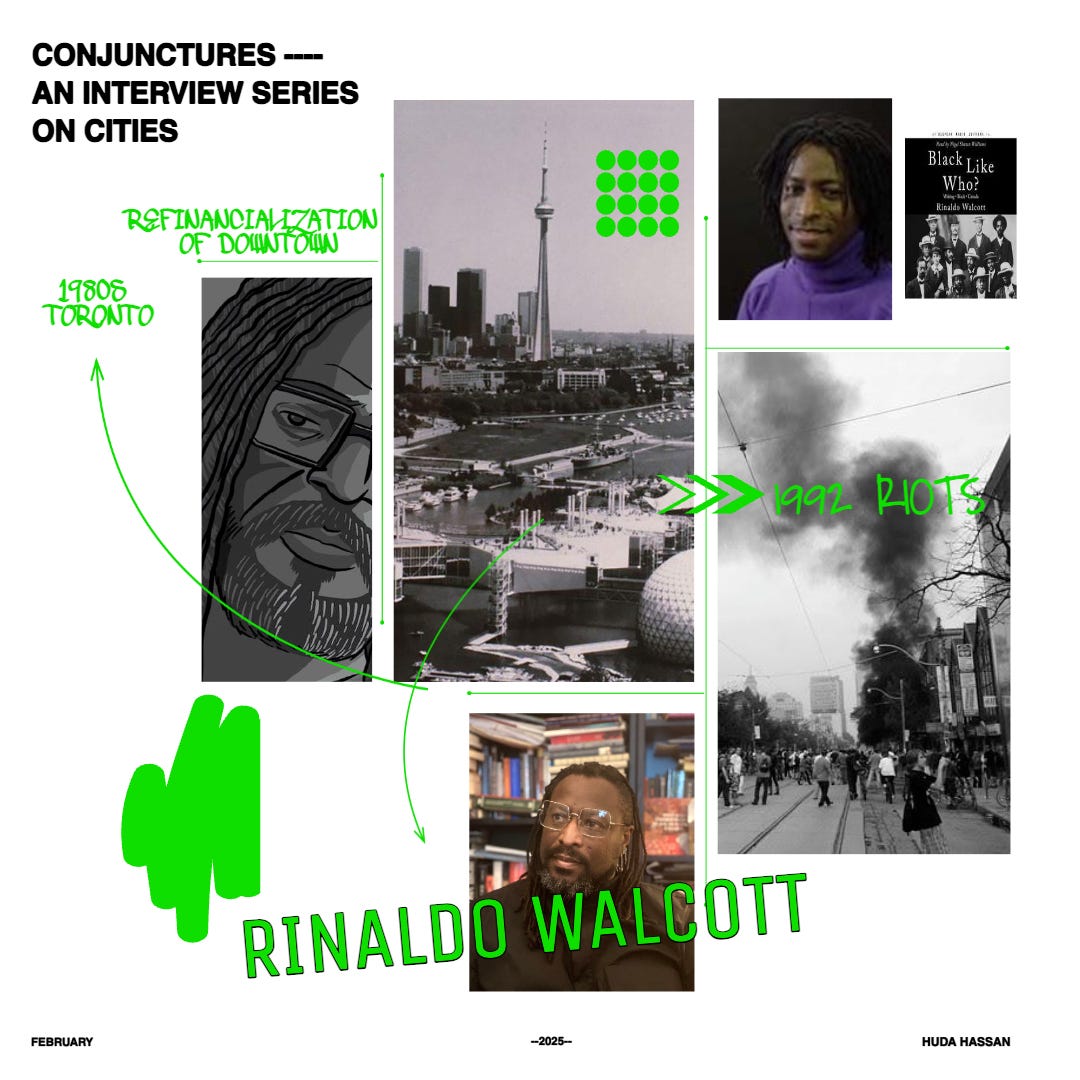

Conjunctures [01]: Rinaldo Walcott on downtown cores of the 1980s

On gentrification in Toronto, multicultural cities, and the relationship between cuisine and theory.

Conjunctures is an interview series on gentrification and the crisis of cities. A conjunctural analysis, as per cultural theorist Stuart Hall, is a combination of circumstances, histories, or events that produce a crisis. Conjunctures is a monthly digital meeting place: artists, thinkers, and organizers prying at the crisis of their city, sharing love notes to intersections. This interview is an introduction to the series.

Rinaldo Walcott — writer, critic, and scholar

For Conjunctures, writer, critic, and professor Rinaldo Walcott talks about gentrification in Toronto and the transformative impact of Queen Street West, particularly in the late 1980s, as a hub for music, art, and (eventually) gentrification. We also talk about how culinary histories shape his theory.

Rinaldo Walcott is a writer, critic, and professor from Toronto. He is currently the Chair of Africana and American Studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo. As an interdisciplinary Black Studies scholar, he has shaped conversations on black cultural politics, liberation, queer life, and diaspora since the 1990s. Black Like Who?: Writing Black Canada (1997), his first book and a seminal text on Black Canada, examined black cultural life under the Canadian conundrum of multiculturalism policy. I met Rinaldo in 2016 when I began my studies as one of his last doctoral students at the University of Toronto.

Huda Hassan: When did your relationship with Toronto begin?

Rinaldo Walcott: I moved to Toronto as a teenager with my mom and dad, who returned to Barbados shortly after. My relationship with Toronto, as an affective sense of this is my city, began when I was 21.

I remember walking along the classic jazz club, The Rex, on Queen West and hearing a noise. It sounded like a scream. I stuck my head in and saw who I would later know as Lillian Allen [the dub poet and writer] performing.

In Barbados, I'd seen many Rastafarians engage in spoken word performance at the edge of reggae and dancehall. But when I moved to Toronto, I wasn’t moving in circles as a teenager, where it was the dominant form of music. When [I saw Lillian], it spun my head around. Queen West became where I would hang out for many years. It's when I made my firm connection to Toronto.

The strip of Queen West — from University Ave to Spadina Ave — was a hub. It extended a bit further and a bit further west until it engulfed all of Parkdale. Between a few blocks, there was a mecca in Toronto. [It was] where you’d run into Molly Johnson or Billy Newton-Davis. Queen West became where I would hang out, but I also worked part-time jobs (at Kinko’s or Alfred Song’s Club Monaco).

If I'm native to any place, I'm native to Toronto — not Barbados, where I was born.

HH: Who was Queen West a hub for, and what changed?

RW: Queen was a hub for music, art, alternative fashion, and what would become an explosive culinary scene. The first French restaurant in Toronto was on Queen. There was the BamBoo Club, which did a fusion of Caribbean food, body, world, and music. It was a hub for bringing together various kinds of creatives and people interested in experimenting in a few blocks full of bubbling, interesting fun. It represented a demographic reality of Toronto: multicultural.

RW: Queen Street of the 1980s was where alternative artists ran, where artists driving culture lived and resided. They lived above stores or blocks behind them. Over the years, it transformed: those artists got pushed further west. What came in was big commercial stores. Cities change, and Queen West is a good example of it.

Toronto became beset by the re-financialization of downtown. In many cities, downtown cores became re-financialized [in the 1980s].

RW: The artists and creative communities are the first to get pushed out. As people pushed along Queen Street West, you mapped its development. Each block an artist was pushed out from [became] the desired block to develop. Queen Street is a good study of the beginning of the transformation of Toronto into a recognizable and knowable global city where stop-in cuisine and a particular nightclub become the markers of what it means to be a big city. If you track those things along Queen Street, you'll get an interesting history of Toronto.

HH: You introduced me to Samuel Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999) many years ago in my first class with you. This ‘re-financialization of the downtown core’ was mentioned then. As you talk about the shift of Toronto, I’m reflecting on how the development of Times Square in the 1970s led to a reorganization of Manhattan’s midtown, erasing a long history of inter-class and cross-cultural communities of contact and communication.

RW: What happened in New York City became the template for how to remake cities and downtown cores. By the 1990s, we saw an interesting shift in Toronto, where black people were emptied of the core. By the early 2000s, black people were gone, except in a few concentrated areas. Now, in the ‘20s, those few concentrated areas — such as Moss Park and Regent Park — are being emptied yet again.

In the 1990s, [the] black people [who] ‘left’ downtown largely worked in the culture industries: artists, playwrights, and those interested in being attached to cultural ferment. But some black people started to flee to the suburbs for complicated reasons, such as policing: if they moved to the suburbs, kids were going to be safer. It turned out not to be true. It was also the desire to have bigger homes. Housing policy cut down the Greenbelt to build more houses in Brampton and elsewhere.

There was a sense — amongst the aspiring black middle class — that living in downtown apartments without backyards didn't show you financially and culturally arrived.

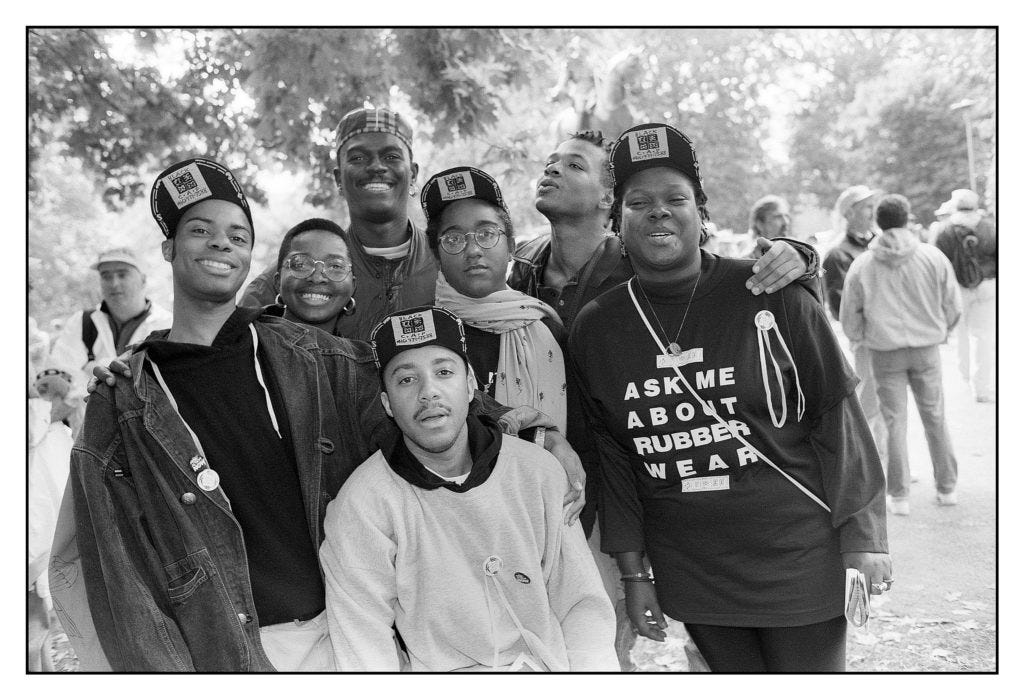

HH: Tell me about your relationship to organizing: your participation in the 1992 Yonge Street Riots (stemming from the 1992 LA Riots) and the 2010 G20 protests.

RW: I have a friend, an activist in the city [who] has grown to become a renowned advocate for black people. We went to high school and university together. I would not have become a professor if she, at the end of our undergraduate degrees, hadn't made a joke: Oh, you're going to have to get a civil service job. It scared the shit out of me. I applied to graduate school that day. It was 1990. This woman is Angela Robertson.

We've been friends since. Even in high school, Angela was an activist, but I didn't understand. I understood it when we were undergraduate students.

RW: Angela was part of the Black Women's Collective (BWC) as a teenager. She brought a poet — Dionne Brand, also in BWC — to campus to read from the recently published book Chronicles of the Hostile Sun (1984/2022). BWC would visit Audre Lorde in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Angela exposed me to the logic of black feminism in profound ways. When I went to graduate school, one of the questions from the ‘80s was: what does it mean to be black in Canada?

I came to Canada knowing quite a bit about the country because of how colonial [Caribbean] education was. Still, I would always encounter people who didn't know much about me, having come from the Caribbean. I asked: what does it mean to be here?

I started to write a dissertation on hip-hop in Canada.

I was sitting at home when the verdict on Rodney King [came in]. I was watching Citytv, which showed the crowds at City Hall. I jumped on my bicycle, rode up, and joined where the breaking of the windows began. I remember the police interventions and running around Bloor, then down Bay Street, to avoid the police. In the years prior, the police in Toronto had shot young black people. Many of us [knew] we could be subject to police brutality, having been stopped and aggressively questioned in ways that threaten potential violence. All of that was in the firmness.

Seeing black people rise in LA in 1992 was an emotional sense of giving it back. Then, it happened in Toronto. It was total bodily exhilaration to be in the company of folks, saying we’re not taking this shit anymore.

I wasn’t an activist, but my work always tracks what's happening to black people — not just in Canada. How does what happens [here] resonate with black people in the US, UK, France, and other parts of Europe? When it comes to housing, employment, and policing, they track along the same lines — especially for poor black people.

I have so many friends who are activists and adjacent to activist formations; I find myself in that mix. When I [first] got hired at York University, I quickly learned the job was not for me; it was for a community of shared political desires. I use my jobs and resources from institutions to share with the community. I dropped working on hip-hop to work on black queer stuff. Black queer people said: you're a queer man, and you should be talking about it.

Activism has been built into [my] scholarship and the decisions I align with. I could end up in the streets being cattle in 2010 [during the G20 protests], which was one of the most terrifying moments of my life.

HH: Are there certain qualities or characteristics you allocate as threaded to Toronto?

RW: The high school I went to was largely immigrant: kids from the Caribbean, Portugal, Italy, a smattering of others, and some working-class “white” Canadian kids. Something interesting happened. In some ways, my peers would have been the first generation to go through the indoctrination of Canadian multiculturalism. That had a profound impact on why I maneuver the world.

I only speak English but feel an affinity with people living in multiracial, multicultural spaces; I take that as a norm. It's something emanating from having come of age in late ‘80s and early ‘90s Toronto: this sense of cross-cultural, cross-racial confidence that allows for fluid engagement with people who are not like you, who you can see, understand, and make sense of as a fundamental part of your community. It imbues my worldview and the way I move in the world.

Multiculturalism policy [in Canada] came into effect in 1971. Those of us in the mid-80s are living it out. By 2001, there was 9/11, an attack on Muslims in Canada, and multiculturalism came to an end. We still talk about it, but it ends. In Toronto — where almost 50% of black people live at or below the poverty line — there's no sense of multiculturalism. It is over.

For my generation, multiculturalism had a formative impact: the work of Cameron Bailey (at TIFF), Clement Virgo’s cinematic work, and Dionne Brand’s novels. You see a certain kind of attitude to multiculturalism: a critique and an assumption of a certain ease, living cross-racially and cross-culturally.

That's what I call the multiculturalism they didn't want to work: the vernacular multiculturalism.

There's no way if you're living next door to Black Muslim people and not hearing or saying ‘Say wallahi.’ This becomes part of our everyday language in Toronto — the multiculturalism the state doesn’t want.

HH: What is the relationship between cuisine and theory for you?

RW: It ties into multiculturalism.

Cooking is about drawing from all your influences, experiences, and encounters — but it must be grounded. My cooking is grounded in nostalgia for the Caribbean, but it's influenced by my encounters with Italy, Portugal, [and other places]. By that, I don't mean having visited those places geographically; I'm talking about encounters in Toronto. In Barbados, you might call it fish cakes. Your Portuguese neighbor calls them Bacalhau.

What cuisine has done for Toronto is that it has expanded imagination but also produced a lot of space for connection. This dish in Barbados, called conkies, is made from cornmeal, coconut, and some raisins. It's made around November 30, Independence Day. I remember in the 1980s, at one point, craving [these] things. My sister would make them, but I had to find the ingredients. I found everything except for one: [the dish] has to be wrapped in banana leaf and steamed. I was able to find it in a Filipino store.

You begin to realize things you think are unique to your own local food culture are connected to other spaces. In the Caribbean, so much of what we eat was brought from elsewhere. It’s not surprising I found it in the Filipino grocery shop.

My thinking about cooking and cuisine is related to a promiscuous theoretical relationship: I'm always interested in finding and drawing from thinkers who advance the political project, who push me to think beyond the limits, creating something that helps us think better about where we are in the moment. It’s the same thing I do with cooking.

HH: If a friend is visiting Toronto, what place would you recommend?

RW: Albert's Real Jamaican at St Clair and Vaughn. If you had asked me this question in the 80s or early 90s, I would have said Bathurst Street, Third World Books and Crafts, the barber shops, or the Chinese Jamaican restaurant that used to be there.

I also have to return to Queen Street. Walk along, even though it's not the street I came of age with. Walk and get to Parkdale, where there are remnants of what the initial street from the 80s used to be. There's still the sense of a creative, inventive play as you get over to Queen and Lansdowne. There's still grittiness and all the ways Toronto polishes itself up with ugly glass tower buildings. It is where there is still interest in the belly that could be pleasurable, violent, or the unknown: what Queen West used to be.

Conjunctures is an interview series on gentrification and the crisis of cities, a digital meeting place. Each month, I’ll interview an artist, thinker, or organizer poking and prying at the crisis in their town, sharing love notes to intersections. The following interview will be in March.