Harlem Roses

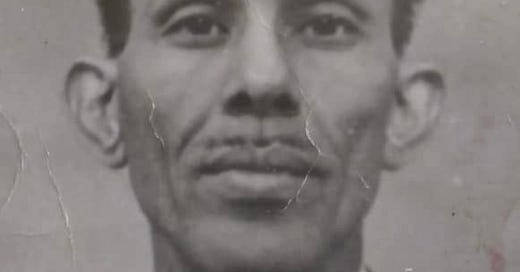

Tracing the Somali Histories of New York City. My latest research project: a close narration of the archives of Somali seafarers in New York City.

This essay introduces my current research project on the unwritten histories of Somalis in Harlem. It is a continuation of the work I published in my doctoral dissertation at the University of Toronto (2023).1 I am now continuing this multi-modal archival work in New York City with the support of NYU Steinhardt and others.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mother, Loosen My Tongue to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.