On Revision and Revising

Revision is as fundamental to creative expression as it is a method to living.

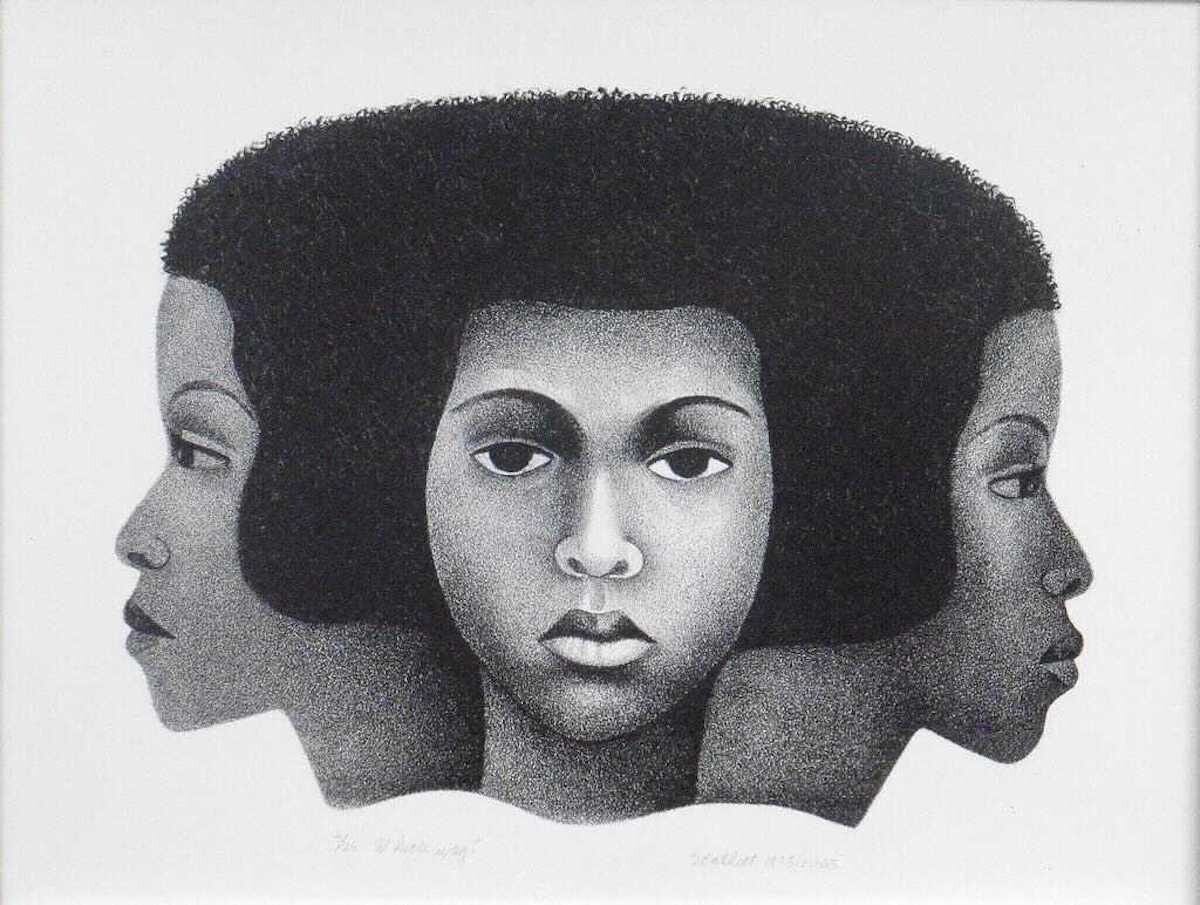

Elizabeth Catlett, Which Way?, 1973–2003. Lithograph, 11 x 14.5 inches, edition 4 of 25.

Revision is as integral to artmaking and creative expression as it is to living. It is a method, a tool for transformation. A raison d’etre, the process loosens the tongue. Revision is not only a tedious creation method, as author Peter Ho Davies explores in The Art of Revision (2019), but a valuable tool in our interpersonal development. Time and dedication is a crucial part of the revision process. He reminds us of this in his conversation with author and professor Kiese Laymon, the author of Long Division (2013) and Heavy (2018), who also urges us to consider revision as therapeutic, drawing out the spiritual. To revise is a practice of witnessing:

I was beginning to understand “revision” as a dynamic practice of revisitation, premised on ethically reimagining the ingredients, scope, and primary audience of one’s initial vision. Revision required witnessing and testifying. Witnessing and testifying required rigorous attempts at remembering and imagining. If revision was not God, revision was everything every God ever asked of believers.

— Kiese Laymon, 20211

Revising is an act of repair. The process reveals the majesty of failure: making friends with mistakes, getting it wrong, consistently going back to try again, failing again, reimagining, all to reconsider new routes. Failures and mistakes are a core part of living. Our revision process reveals us to ourselves, helping us contend with the ego rooted in the fear of failure. You revisit, rethink, repair, and practice the act of witnessing. Revision is a declaration of love, requiring time, commitment, a zeal to keep striding. Revision is repetition, which is also study.

I’ve been teaching the visual works and ideas of Lois Mailou Jones to students in New York for a few years now. An artist, educator, and unsung Harlem Renaissance figure, her work expanded across costume creation, textile designs, watercolors, paintings, and collages. As she examined in her 1989 interview in the Callaloo: A Journal of African-American and African Arts and Letters, her exposure to the world enriched her visual style and approach, offering notes on revision in her approach to craft.

During the onset of the Renaissance, Jones developed as an artist through various visits from Boston to Harlem. Facing the limitations of the American art world for the black artist, she traveled extensively abroad, earning a fellowship to study in Paris at the Académie Julian in 1937: an exodus similar to many of her peers who felt the weight of America’s institutional and racist limitations. It was in Paris where she could exhibit her work, where Baldwin, Baker, and so many others flocked — despite Hughes cautioning his peers in 1924: “But about France! Kid, stay in Harlem!”2

After completing her studies in France, Jones made several detours and reroutes to Haiti, longing to be energized by witnessing her indigenous art forms. (Jones would not arrive in Africa to study the arts until 1970). She was a product of Alain Locke, the Dean of the Renaissance, who proposed to artists of the 20th century to embrace their heritage: where and how can black visual artists revise their work to return to Africa?

In her 1989 interview with Callaloo, Jones talked about his influence:

“It's been a pretty hard road, but I haven't allowed it to make me bitter. I've tried to live above that. I think many things were conducive to that. For example, when I came back from France, the first person I met on the campus at Howard University was Dr. Alain Locke, who greeted me by saying that he had followed my career in Paris and that he was using one of my paintings, a street scene in Montmartre, in his book. But he insisted that black artists have to do more with the black experience and, especially, with their heritage. He brought up the fact that Matisse and Modigliani and Picasso and so many of the French artists were getting famous by using the African influence in their work and that it was really our heritage and that we should do something about it. What Dr. Locke said caused me to turn to the black subject, and one of the first paintings I did was Jennie, a very strong impressionistic portrait of a black girl cleaning fish. That painting was used in Alain Locke's exhibit in Albany, which he organized and curated.”

— Lois Mailou Jones (1989)3

Alain Locke’s seminal text, The New Negro (1925), was a text proposing revision, asking for artists and community to leave behind the ‘Old Negro.’ Locke epitomized Harlem’s renaissance through an anthology of artists, poets, and writers — Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and Claude McKay and the novelists Rudolph Fisher, Zora Neale Hurston, and Jean Toomer, to name a few — to reconsider a shift towards the vitalization of the New Negro. Like his contemporaries, such as W.E.B. DuBois, Locke called for using art as propaganda. A new culture of creative assertiveness and self-confidence, avoiding parochialism and propaganda, questioning and eschewing tradition and eurocentrism in aesthetic standards, and creating racial pride, self-expression, and experimentation. Locke penned five essays for the anthology. His most powerful, “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts," argued that the art of Africa possesses the same intricacies and profundity as the art of the classical antiquity.

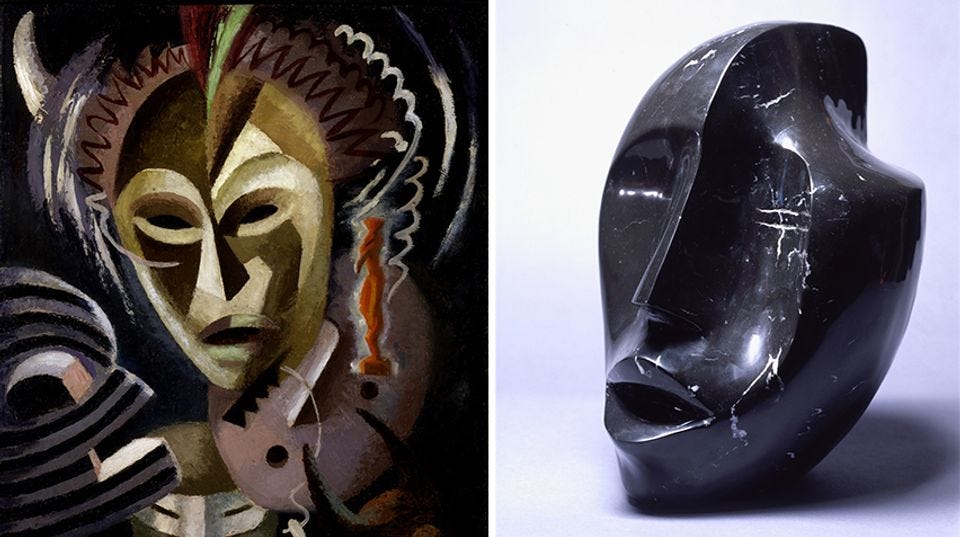

Loïs Mailou Jones, Les Fétiches, 1938, oil on linen, 25 1⁄2 x 21 1⁄4 in. (64.7 x 54.0 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Jones explored ancestral roots through her play of masks, a repeated sight and theme in her long body of work. Her obsession with masks began in high school when she met Grace Ripley, a designer and professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. Eventually, after studying continental artists, the African mask became her best opportunity to study the mask as a form. However, after producing her piece ‘Les Fetiches’ in 1937, her peers had questions.

“I'm very fond of Les Fetiches. I did that painting in Paris in 1937. I remember taking it down to the Academie Julian to my professors: they all looked at it, they looked at me, and they said, "Mademoiselle Jones, it does not look like you. You paint the Luxembourg Gardens and the Cluny Gardens and the streets of Paris. What are you doing?" So I said, "Well, when you look at Matisse and Picasso and Modigliani and all the others using the African influence, don't you think that if anyone has the right to use it I should have the right?" So they said, "If anyone has the right to use it, she has.”

— Lois Mailou Jones (1989)

Jones continued to revise her approach to studying the mask from the lens of Africa. She eventually compelled students to examine heritage, as per Alain Locke, when she later served as a dean at Howard University’s Arts faculty for nearly fifty years and helped develop art departments across America. During her tenure, she made her first trip to Africa, traveling between Mali and various countries to teach and learn from different artists, implementing Locke’s legacy of African ancestral arts into her work, impacting her students and emerging artists of the time. In her 1989 interview, Jones said:

“I brought back all of that material which is now in the archives of Howard University. But what I marveled at was the beauty of the mask, which had started with me when I was young in Boston when I worked with Grace Ripley. In Africa, I would go to the museums and make sketches and studies from the fetiches and the masks and use them in my creative paintings. I found in many of the masks the importance of the eye. Many of the paintings are built on the beauty of the patterns found in African design. One of the paintings you said you liked—Les Ancestors—was inspired by the "Dogon" door. All of those many little ancestors represented in the painting are an example of my creative expression.”

— Lois Mailou Jones (1989)4

One of Jones’ students was Elizabeth Catlett, an American and Mexican sculptor, graphic artist, and activist — a Black revolutionary artist and all that it implies, as she proclaimed in 1970 — best known for her depictions of the transnational Black woman’s experience in the 20th century. Her work was inspired by the Black Arts Movement, her teachings by Lois Mailou Jones, Mexican muralism, and pre-Hispanic sculptural language. She eventually relocated to Mexico in 1947, joining Taller de Gráfica Popular, a radical left-wing printmaking collective.

Loïs Mailou Jones, Untitled (Two Women), c. 1945, the Baltimore Museum of Art © Loïs Mailou Jones Pierre-Noel Trust

I recently went to Catlett’s exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. I was moved by the collaborations, influences, and repetitions between her work and Jones's. Momentarily, I got lost in the shifts and revisions of her work. Catlett’s work throughout the decades waded and examined the mother-daughter dyad through various series. Her MFA thesis, ‘Negro Mother and Child’ (1940), studied her limestone sculpture, focusing on the figuration of a Black mother cradling her daughter: two separate bodies molded into one. This repeating thread in her work met various interruptions. Cartlett partially completed her thesis as a graduate student at the University of Iowa: barred from living and working on the campus as a black woman, she completed her work with severe limitations.

The most glaring calls to revision are intergenerational. Fed up by the ceilings America designs for many, Cartlett fled, denouncing her previous home. After becoming a Mexican citizen in 1962, she was declared an ‘undesirable alien’ in the United States, impacting her presence during the Black Arts Movement and prohibiting her from visiting her ailing mother. She renounced her American citizenship, trading it in for the ability to focus on her work, values, and the struggles of working-class people across the continent.

Sitting with the works of Jones and Catlett is to sit with the power of revision. A close study of Cartlett and Jones’ work reveals repetition, or what Amiri Baraka called a ‘changing same,’ deploying ancestral methods, aesthetics, and approaches to their work and living. A key ingredient to their repetition required revision: revising where they considered home, methods of expression, and the roots of their ancestry and activism. Both Catlett and Jones used revision in their artmaking and, presumably, in their interpersonal lives as a step towards repair.

Revision is repair, too.

When I stood before Catlett’s 16-page thesis, examining and imagining the mentorship and links between herself and Jones as an educator, a deeply buried feeling swam to the surface. I’ve been revising it since.

For a long time, my writing was geared towards Toronto and its artistic and political history. At the time, I didn’t imagine leaving my hometown. I also didn’t anticipate struggling to find work and ways to economically sustain myself like I did the decade before I left.

Toronto is a city eating its own, becoming a playground for expats and the rich — similar to so many other major cities. Moving away resolved many of those limitations and opened my eyes to how narrow-minded my imagination was at home. When you’re stuck in a city for too long, you forget there’s a world, one offering beauty, shared problems, and alternative possibilities.

I ended last year revising why I sometimes feel lost in this transition, a feeling of limbo: somewhere between student and teacher, mentor and mentee, settled and unsettled, immigrant yet privileged westerner; complicity and advocacy. I don’t know where my work is going. But I know in my continuous revisions of my intent, I remain steadfast, focused, and committed. I revise my craft and life—who and what is this writing for? I’m trying to reimagine the ingredients. Until I do, I’ll revise, revise, revise, with hopes of repair.

Laymon, K. (2021, May 10). What we owe and are owed. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/22419450/kiese-laymon-justice-fairness-black-america

Hughes to Countée Cullen, March 11, 1924, CCP, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

Rowell, Charles H. "An Interview with Loïs Mailou Jones." Callaloo 39 (1989): 357-378.

Ibid.

Fantastic perspective! You’re a great writer. Keep sharing with us!

Exceptional as always (and w perfect timing)

So good